Airway Management: A Guide

Airway management is one of the core competencies in emergency medicine, as no effective ventilation or adequate gas exchange can be guaranteed without open and secured airways. Modern approaches are used to ensure pulmonary oxygenation and reduce the incidence of hypoxia-associated complications, increased mortality, and potential secondary injuries. These are based on evidence-based guidelines that promote practice-oriented application.

In this article, you will learn everything you need to know about airway management: from a clear definition and main indications to key measures for securing airways.

Definition of airway management

Airway management covers all actions aimed at ensuring the patency of the airways and guaranteeing sufficient spontaneous breathing or external ventilation.

The primary aim is to maintain ventilation and an optimum oxygen supply, especially if spontaneous breathing is impaired. This is frequently the case in emergencies, if a patient has suffered serious injuries, or during perioperative phases.

S1 Guidelines on Airway Management

The S1 Guidelines on Airway Management 2023 from the German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (DGAI)1 emphasize that timely, precise airway management adapted to the clinical context is crucial. They serve as evidence-based guidance for medical personnel to safely and effectively apply suitable techniques and strategies for securing airways in various clinical scenarios. The focus here is on reducing potential complications and maximizing the probability of survival and patient-specific quality of care.

Indications

Airway management plays a central role in emergency medicine, emergency medical services, intensive care medicine and anesthesia, as it forms the basis for sufficient oxygenation and ventilation.

In a prehospital context, effective airway management is often crucial for the survival of patients during cardiopulmonary resuscitation or emergency anesthesia and in cases of severe trauma.

The most important indications include:

Respiratory insufficiency:

In respiratory insufficiency, the lungs are unable to ensure an adequate supply of oxygen to the body (hypoxemia) or effectively remove excess carbon dioxide (hypercapnia).

Aspiration danger/ Risk of airway obstruction:

For patients with an increased risk of aspiration, for example due to food, fluids or vomit, there is an acute danger of airway obstruction. Airway management prevents airways from being blocked by foreign bodies or aspirated materials, thereby minimizing the risk of serious pulmonary complications such as aspiration pneumonia.

Traumatic injury to the head and upper airways:

Trauma in the head and neck area, such as fractures of the facial skull or swelling of the upper airways, can significantly impair breathing.

Airway management measures

Airway management involves various measures to open and maintain airways and enable unobstructed breathing. These range from basic manual techniques to invasive procedures and are selected on the basis of the clinical situation and urgency.

Commonly used methods include the cross-finger technique, where the thumb and index or middle finger are used to open the mouth and also the airways, and the head tilt/chin lift(HTCL) maneuver, where the person’s head is tilted back to clear the airway – especially in unconscious patients with no suspected spinal injury

The jaw thrust maneuver on the other hand, keeps the airway open without endangering the cervical spine. It is particularly useful for patients with suspected cervical spine injuries.

In addition to opening a patient’s airways, it is also important to keep them constantly unobstructed. In many cases, the stable lateral recumbent position is used as a positioning technique, especially if artificial ventilation is not possible or necessary. It prevents patients from aspirating vomit or fluids and ensures that their airways are temporarily clear. If any airways are blocked by secretions, blood or foreign bodies, airway suctioning is performed.

Depending on the severity of the airway disorder, non-invasive ventilation procedures using ventilators or invasive techniques such as intubation are used. The choice of method depends on the urgency and the patient’s condition.

Ventilation in conjunction with basic airway management

With basic airway management techniques, there is no direct intervention in the airways.

Bag-valve-mask ventilation

A classic example of this is manual mask ventilation, where a bag valve mask (BVM) is used to insufflate oxygen into the lungs through compression of the bag.

It is mainly used at the beginning of a ventilation session. However, one study showed that patients who were treated with BVM ventilation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation had lower ROSC and survival rates than patients with a tracheal tube and supraglottic airway management.2

In addition, BVM ventilation exhibits limitations in its effectiveness and ventilation during prolonged transportation times or serious airway disorders. This technique achieved less successful results than endotracheal intubation (ETI) during longer transportations.3

Invasive airway management

During invasive airway management, airway devices are used to directly secure the airway. Invasive ventilation is essential in cases of severe respiratory arrest or inadequate BVM ventilation.

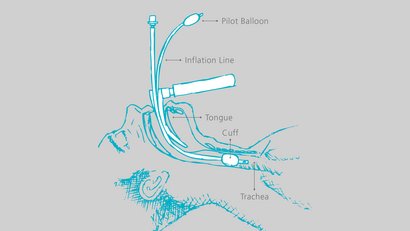

Tracheal tube (gold standard)

The tracheal tube is considered the gold standard for airway management and involves inserting a tube directly into the patient’s trachea via their mouth or nose. At the end of the tube is a cuff, which serves as protection against aspiration.

Studies show that the tracheal tube achieves significantly better results in terms of oxygen supply and ventilation than other methods, especially with longer transportation times.4 It also leads to higher ROSC rates and a better survival rate during resuscitation.5

However, intubation also involves risks, as success rates in studies vary widely (51–98%) and therefore results should be interpreted with caution.6 One study also showed that there was no significant difference in neurologically favorable survival rates between endotracheal intubation and patients treated with bag-valve-mask ventilation.7

Supraglottic/extraglottic airway management

If endotracheal intubation is difficult or not feasible from a time perspective, supraglottic or extraglottic airway management can be a useful alternative. These airway devices are placed above the trachea to keep the airway open.

They are quicker to position and require less experience than a tracheal tube. However, they do not offer reliable protection against gastric insufflation or aspiration, particularly in the context of emergency ventilation. The most common airway devices for supraglottic airway protection include:

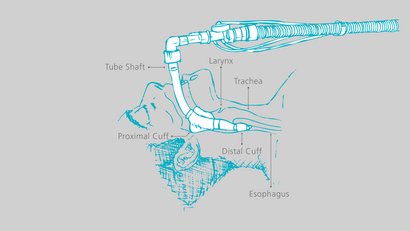

Laryngeal tube

The laryngeal tube has two cuffs. A large cuff (proximal cuff) seals the naso-pharyngeal cavity, while a smaller one (distal cuff) seals the entrance to the esophagus.

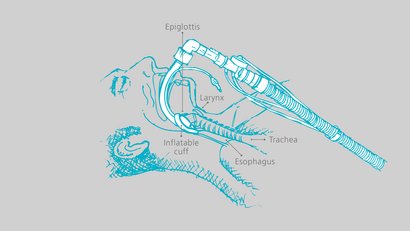

Standard laryngeal mask airway (LMA)

The laryngeal mask airway is a mask with an inflatable, oval or teardrop-shaped attachment at the end and a valve to regulate the cuff. It is placed in front of the larynx.

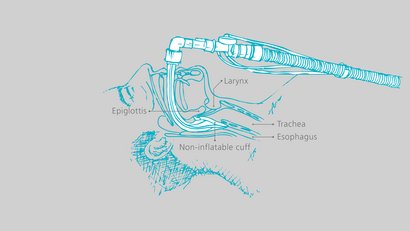

i-gel airway

This advanced version of the laryngeal mask airway has a non-inflatable seal that fits snugly over the larynx due to its gel-like texture and minimizes compression and displacement trauma.

The laryngeal tube, LMA and i-gel airway can be used as alternative emergency airways. In difficult conditions, when mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation are not possible, these methods can be an alternative.

A study shows that supraglottic airway management achieves a higher ROSC rate in resuscitation patients than BVM ventilation.8

However, supraglottic airway protection has less positive effects on long-term survival and also exhibits less favorable neurological outcomes compared to endotracheal intubation.9 Researchers have also found that ventilation with supraglottic or extraglottic airway management is not always optimal and can compromise the air supply in complex emergency situations.10

Hybrid solution

If direct intubation is not possible at first, supraglottic airway management (e.g. laryngeal mask airway, laryngeal tube) is used as a temporary measure to gain time and create the prerequisites for intubation. As soon as the situation is stabilized, intubation is switched to a tracheal tube to ensure the airway stays open in the long term and ventilation is optimal.

Coniotomy/tracheostomy

If conventional measures fail, performing a coniotomy as an emergency procedure or a tracheostomy as a surgical procedure may save the patient’s life. These procedures provide direct access to the trachea, but are risky and require highly qualified personnel.

Airway management for difficult airways

A difficult airway occurs when unexpected or foreseeable complications occur during airway management that make the use of standardized techniques such as mask ventilation or endotracheal intubation considerably more difficult or impossible.

This may be due to anatomical abnormalities (e.g. macroglossia, retrognathia), pathological changes (e.g. tumors, edema, trauma) or functional limitations (e.g. reduced mouth opening, restricted cervical spine mobility).

If a difficult airway is anticipated, careful preoperative evaluation using a Mallampati score or Cormack-Lehane classification, for example, is essential. Alternative strategies should be defined in advance and appropriate devices (e.g. video laryngoscope, flexible intubation endoscopes) should be provided.

In acute emergency situations or in the event of unexpected difficulties, a structured approach based on algorithms such as the Difficult Airway Algorithm is essential.11

Airway management with WEINMANN

Clearing and securing airways are important measures in airway management.

With its ACCUVAC Pro portable suction device, WEINMANN offers a powerful yet intuitive solution. Thanks to its high suction power and easy handling, the device enables quick and effective removal of secretions, blood and foreign bodies – from both adults and children. With 4 individually adjustable suction levels, ACCUVAC Pro is an indispensable companion both in emergency vehicles and precarious environments.

In addition, our MEDUMAT Standard² and MEDUVENT Standard ventilators offer versatile solutions for invasive and non-invasive ventilation in emergency situations. They can be combined with a wide range of respiratory aids so that EMS field providers can react quickly and flexibly to the individual needs of patients.

MEDUMAT Standard²

With an integrated rapid sequence induction (RSI) mode, the device offers safe and controlled ventilation during anesthesia induction with medication. Manual ventilation using MEDUtrigger supports the use of a wide range of airway devices.

MEDUVENT Standard

This device performs particularly well in extreme situations with up to 7.5 hours of self-sufficient ventilation with no external compressed gas supply. This makes it perfect for use in remote areas or in logistically challenging situations. Here too, the manual mode via MEDUtrigger supports the use of a wide range of airway devices.

In emergency situations, the right technology is essential: Devices such as MEDUMAT Standard² and MEDUVENT Standard precisely secure airways, prevent complications and ensure optimal oxygen supply, even under extreme conditions. Both devices maximize patient safety thanks to their intuitive operation and comprehensive monitoring functions.

WEINMANN not only offers you state-of-the-art medical technology, but also comprehensive advice. Our team of experts is on hand to help you find the right solution for your specific requirements. Book an appointment today for a personal consultation and benefit from our expertise.

Customer Service (International)

- Phone:+49 40 88 18 96 - 0

- Email:Please enable JavaScript to render this link!

1 https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/001-028l_S1_Atemwegsmanagement_2023-09.pdf

2 Tang et al., Outcome of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation with Different Ventilation Modes in Adults: A Meta-Analysis (2022).

3 Song et al., Association Between Prehospital Airway Type and Oxygenation and Ventilation in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (2023).

4 Song et al., Association Between Prehospital Airway Type and Oxygenation and Ventilation in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (2023).

5 Tang et al., Outcome of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation with Different Ventilation Modes in Adults: A Meta-Analysis (2022).

6 Wang, Wei, Xiaojing Zhang, Minqiang Liu, and Xue Han. "Comparing Effectiveness of Initial Airway Interventions for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Clinical Controlled Trials.”

7 Jung, Eunjung, Hyeon-Ju Kim, Hyeong-Joon Lee, et al. "Association of Prehospital Airway Management Technique with Survival Outcomes of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Patients.”

8 Wang, Wei, Xiaojing Zhang, Minqiang Liu, and Xue Han. "Comparing Effectiveness of Initial Airway Interventions for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Clinical Controlled Trials.”

9 Jung, Eunjung, Hyeon-Ju Kim, Hyeong-Joon Lee, et al. "Association of Prehospital Airway Management Technique with Survival Outcomes of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Patients.”

10 Song et al., Association Between Prehospital Airway Type and Oxygenation and Ventilation in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (2023).